Unlike First Lady Michelle Obama, I can honestly say that I have ALWAYS been proud of my country. But today, despite the worshipful words and idolatrous phraseology toward Barak Obama from those not possessing a biblical worldview (and from those who perhaps do), I am very proud to be an American. An African-American? Perhaps. Well, maybe more than I will care to admit. Unlike so many of my African-American "brothers and sisters", I have never thought it prudent to be Black first and to be a human being second. Somehow, I always knew who I was and who my God is!! It has never bothered me that 43 of our country's presidents were white men. Political office was never a validation or proof of equality.

But be that as it may. It is a time for all Americans and well-wishers to be hopeful and prayerful for Barack Hussein Obama.

Many African-American churches are in full praise tonight and will be throughout the week. I have asked the Lord for extraordinary and uncommon wisdom for this president. Because it seems to me that if he has nothing else, with wisdom he will have just about everything he needs to lead and govern. How about you? I think guys like Joseph Farah, whom I respect, are in the end, misguided in praying for Obama to fail.

Sure, I'd have rather he had been a conservative and more biblically aware and grave, and because he is not, I am rather saddened for our nation's sake. The challenges before us will only be solved by a man God appoints who loves him, loves his people, and his word. Of course Obama doesn't fit the bill. But we may hope and pray a worse man doesn't come along to wreak havoc, either. After all, Jacques Necker was better then Danton, who himself was a choirboy compared to Robespierre during the Terror. And of course, Madame de Stael said Napoleon was essentially Robespierre on horseback - and millions were slain under Monsieur Bonaparte. So there could be worse presidents than Obama. But alas, I feel the ill winds blowing, too. What on Earth can be done amidst so much Obama-worship?? This part is not good.

Nevertheles, I hold out hope. Abe Lincoln changed while in office from his "House Divided" 1st inaugural speech to his 2nd inaugural speech of full acceptance of the Lord's justice in bringing the Civil War about. Anne Applebaum of the Washington Post likens President Obama's task as that of the pilot of Flight 1549. He's gonna need some SKILLS.

So I have to tell myself - things can change!

It seems that so many Dr. King analogies and remembrances have been raised it is appropriate - I guess - to throw in my two cents. I will attach - as soon as I can figure it out - the Prologue and Chapter One of my doctoral dissertation written in 2005. Check it out. Ignore the big words, will you?

Prologue

A Call to Righteousness: Reviving the Imago Dei

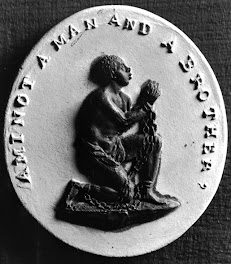

The Civil Rights Movement marked a watershed period of American History. Indeed, throughout the world, the movement itself inaugurated a change of heart and direction in the cause for the equality of humanity. The movement also answered forcefully the question of the Imago Dei. Are all men created in the Image of God? For up to its genesis, the resounding non-answer from perhaps the freest nation in the world was that men were not all made in the image of God. The presuppositions of the day, rooted and grounded as they were in science, existentialism, naturalism, and in evolutionary doctrine, were foundationed upon the belief that mankind was by and large an evolutionary accident. On the other end, the opposition to this party line, the Christian Church, lay dormant and tepid – and without a vigorous challenge to this view. In fact, one of the repeated lessons of the history of the Church was that wherever she was challenged in her worldview by the science and philosophy of her day, in time her retreat was an inevitability. It is one of the more shameful chapters in her history to note her active participation in the denial of the equality of being, worth, and ability of so-called Black, dark skinned believers, and believers of color. The enforced racial segregation of her own flock, the denial of equal status in her pews, and the rejection of equal access to her sanctuaries were denied not by belief or doctrine but by virtue of race and ethnicity alone. In the pages to follow I will discuss some of the historical and philosophical issues raised by the rejection of the equality of mankind and the Imago Dei.

This paper is mainly an historical survey. But it is a survey of history informed by theological and philosophical ideas and perspectives relevant to the Image of God worldview as set forth in the Bible. I am, as outlined in the scope of the work, embracing the view that the Church – evangelical and conservative – remains the repository of active belief in God and it has been given solely to her, by Christ Himself, to act as the heaven-birthed agent of moral righteousness in the land to call to account people and institutions involved in unrighteous practices in the mistreatment and indignities human beings have suffered through racism and ethnocentricism. Hence, the view that I am taking that while not all American churches have historically embraced the ethnic and racial segregation of the past - most have. Although a church body may be ethnically segregated it does not follow that it is ipso facto a racist institution. But it is the purpose of this paper to be a small contribution to the body of knowledge that recognizes the fact that most churches have indeed been passive bystanders if not inheritors of racism, ethnic thought, and racist ideologies, for good or for evil, throughout their denominational or cultural history. I will also attempt to show that embracing these ideas have involved the shaking of the very soul of the nation. These ideas have hindered its moral growth, its unique moral development as a champion of the Imago Dei, its pursuit of biblical human rights and biblical human liberty, and ultimately has rendered null and void its advocacy for the pursuit of justice as God would ordain through Christian life, liberty, and love. This paper is about America and what she inherited and embraced. It is also a call for the churches of America to regain their voice and vocabulary on race and ethnicity and understand what it means to be different yet acceptable by God; to be of a different nationality, but also be a part of the kindred of God from every nation, tribe, and tongue that glorifies the Lamb of God (Rev. 5:9).

Chapter One

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Speech in Washington, D.C., 1963

Every significant social movement has a turning point. The point at which the Civil Rights Movement emerged from a regional anti-discrimination movement to a nationally endorsed social drive toward racial equality can be plausibly traced to the famous “I Have A Dream” speech that Dr. Martin Luther King gave to a national audience in Washington, D.C. in 1963. The occasion for the speech was the culmination of a civil protest march on Washington originally organized by A. Phillip Randolph, president of the Sleeping Car Porters Union, but later becoming the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The context of the speech was framed as the oratorical finale of the event in which Dr. King, on public display for the first time before a national audience, echoed the prevailing themes of America’s rich heritage. It is no doubt true that he had a familiar name and that many people knew of the particular quest of the Civil Rights Movement, still the nation had yet to hear the depth of his passionate vision of America, his underlying affirmation of America as the Good Nation, and his willingness to allow the citizens of the nation to entertain, for a moment, the “better angels” of their collective natures. It was a triumphant speech. Using the stylistic flavorings of the old southern Negro preacher, with its rhythmic call-and-response pauses, King’s words reflected a fresh mix of the articulate scholar/ poet whose poetic remembrance of national goodness and exhortation to further glory called America to imagine that the world of racial equality was nothing to be feared. In effect he asked America to share in his imagination, in his dream, of a reality not yet lived out. His audience, by the power of the Spirit’s presence, was attentive and receptive. Indeed, it was listening to a call to an ontological dynamic that would require national cooperation and will. The Church had not responded to King’s call to brotherhood in the image of God, so the nation itself would be called to give Dr. King a hearing. His moving recitation of the familiar anthem, “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” set the tone. The speech was a marvel of rhetorical skill and improvisation:

“My country ‘tis of thee

Sweet land of liberty

Of thee I sing

Land where my fathers died

Land of the pilgrim’s pride

From every mountainside

Let freedom ring! 1

… And if America is to become

a great nation… this must be true.”

King here implies a universal understanding that the potential for the nation had not yet been attained. Indeed, the race question was a difficult question that had been with nation from its beginning2, and he suggests here that it was perhaps the struggle that would have to be overcome in order to achieve “great nation” status. The prerequisite for such a change of mind and heart, King suggested, are awakened consciences and the collective will to achieve what the consciences have determined to be just. This “achievement” would serve as a catharsis – a purging of past sin – and a repentance - a resolve to never go back to past injustices. And this was the key point in the construction of King’s appeal to the American conscience. It must be noted that King was willing to grant what a great many in the African-American community would not grant: the belief that whites could and would change their minds on the question of racial equality.

“I have a dream today… that this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”3

The appeal to the Enlightenment presuppositions of the country’s principal founding document was King’s brilliant reminder of the raison d’etre of America. It was never the case that men were to be treated as inherently inferior beings on the shores of America. Quite the opposite was true. The United States of America was to be unlike any other nation that had ever existed. Prior to its revolt, the Founders appeal to the British Crown and to the British Parliament was against excessive taxation, taxation without representation, and against unilateral property seizures by the government. All appeals were made with a unique Enlightenment concept of liberty in mind. This concept, instantly recognized as the philosophical ruminations of John Locke and Edmund Burke, was unwelcomed by an authoritarian Crown buttressed by the divine right of kings. Contrarily, this concept demanded that equality of persons be an a priori concept by which people may assent, discuss, debate, protest, and make justifiable violent coercion if necessary to secure their liberties. The history of Western Civilization, of which it may be said that America is a logical heir, is littered with conceptual ideas such as liberty and freedom – often compromised - yielding to the cold harsh reality of facism, feudalism, and militarism. Defiantly, and accepting the historical challenge, the Declaration of Independence thumbed its nose – so to speak - at historical precedent. There is little doubt that Thomas Jefferson spoke for all dissenting Americans against British control in the general thrust of the document’s tenor. Protest gave way to a yearning for independence; independence was in turn to bring about a liberty that could truly be lived out and experienced. But it is ironic that the generations of Americans who have come to a collective assumption of the “rightness” of the founding documents and their declarations of conceptual equality have differed as to their true meaning. For all practical puposes, Dr. King’s true meaning certainly differed from that of Andrew Jackson’s, whose own true meaning would differ from Abraham Lincoln’s. And from both the philosophical and political vantage points, the differences are vast. Literary criticism might point out the fundamental differences between the categories of meaning that words have from generation to generation. Indeed, structuralism as a linguistic category assumes that the phraseology of the Declaration of Independence is fixed in a time in which Enlightenment thinking predominated and in which a concept such as a “self-evident truth” made perfect sense, but in no other time period would it resonate. (In only 70 years that very same concept was thought absurd by no less than the governor of South Carolina!) I will discuss the philosophical and political problems and objections to the concept of self-evident equality of creation in another chapter. But suffice it to be said that Dr. King’s appeal to credal integrity was made to a citizenry convinced of the “correctness” of the Declaration of Independence. This was an American citizenry moved and convicted – as Americans were before and during the period of the Civil War - by both the Christian biblical tradition and the very real power of the Holy Spirit.

“I have a dream that one day the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveownwers will be able to sit down at the table of brotherhood…”4

While the Christian church and its traditions have historically confessed to the universal brotherhood of mankind, the traditional practice has not been a tidy one. There have been, during the Church’s history, numerous debates over the extent of that brotherhood. Some views have held to the notion of the elect only, that is, those who are saved in Christ, as the only true brothers and everyone else, i.e., the lost and unsaved, as outside the bounds of the privileged relationship. Yet the Bible itself is not ambiguous about the fact that all of mankind share a common set of first parents created by God: Adam and Eve. However, the idea of relatedness with which brotherhood has become synonymous loses some of its meaningfulness in any cursory examination of the Old Testament. The Bible tells us that the introduction of sin into the world germinated into a generational and collective hard-heartedness within mankind toward his Creator. As it followed, the breakage between man and God led to a breakdown in the relationship of man and man - to become a man versus man world. National pride, hatred, envy, and idolatry have always been the successful formulas for wars of aggression, oppression, and annihilation. This absence of goodwill and love between nations, given a political articulation by Thomas Hobbes, the author of The Leviathan, was mostly gloom and doom. It formed the basis of German/ Aryan Realpolitik, for example, and inspired the darkest aspirations of struggle as characterized in Friedrich Nietszche’s "Will to Power" theses. But the antithesis of this state of affairs, the conditions of peace and brotherhood among men, even from Christian and Christian-informed worldviews, had been cast primarily in eschatological terms and conditions, as in the Millennial reign of Christ, for example, where the brotherhood of men is immanently enforced, or in the vastly implausible Christian dominion theology.

Dr. King does not spell out the specifics of the conditions of brotherhood he envisions in this speech, but merely assumes a change of the times that neither slave nor slaveowner, racist or humanist, could have envisioned. The audacity of his “dream” bears our deepest consideration of the times as they were. The post-World War II American hegemony produced by victory over facism in turn brought about a triumphalism of American ideals and values – a type of Pax Americana. But it also placed the nation in a uncomfortable conundrum. Having its domestic laws and values scrutinized and taken seriously by an international community forced to come to grips with long denied concepts of freedom, liberty, and righteous brotherhood, America was discovered to be in embarrasingly short supply of its own ideals that it both claimed to cherish and fought to export. In reality however, American culture and laws at that time accurately reflected the collective hearts of its people. And what became clear to many people outside of Black America was that the nation had not sufficiently demonstrated in any serious domestic sense the values it sought to carry to a needy world. Lacking leadership in this new role, the country instinctively exported the one known moral commodity that it had in abundance - the gospel message. Sure enough, after World War II Christian churches mobilized and ramped up their mission work abroad. By 1949, almost overnight, Billy Graham became an international sensation. His compelling presence and oratorical intensity served as a conduit of the good news of the Cross and of the Redemption of mankind and was fully capable of meeting individual human needs5. But for a world seeking acts of Christian demonstration from an ostensibly Judeo-Christian nation, there was still much work to be done. The American domestic zeigeist, a collective conscience that Lincoln believed that all Americans had in common, was no longer able to live with the tension of this unresolved question. The gospel preached abroad and at home compelled the need for national reconciliation on the race question. Thus, the call to moral cleanliness was revived and intensified. Moral values exported abroad – it was sensed - would have to be practiced at home. If the parable of the good Samaritan had any relevance whatsoever, it could certainly be applied to the American Negro and his oppressed condition within the United States. With the “Negro Question” having become increasingly an international embrassment, it was clear that the nation could not continue to point the moral finger at the mote in its neighbor nation’s eyes while ignoring the beam of racism in its own eyes. It could not repudiate Hitler and the horrors of the Holocaust in bloody sacrifice without repudiating George Wallace, Bull Connor, the Ku Klux Klan, and the regular lynchings of Black folk in the South. It was a nation in the midst of self-evaluation that saw the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement, what I will herafter refer to as the Racial Equality Movement: a Spirit-led force of bold, non-violence; of calm ministerial confrontation whose message resounded with the deep spiritual resonance of biblical social justice now. Its contention was simple: genuine conviction from the Spirit must be accompanied by action. Its message: individuals must join together to publicly assent to the message of truth and moral cleansing in order for moral cleansing to become a living reality and for truth to take hold in the streets. King himself put it this way:

The primary reason for our uprooting racial discrimination [racism] from our society is that it is morally wrong. It is a cancerous disease that prevents us from realizing the sublime principles of our Judeo-Christian tradition. Racial discrimination [racism]…relegates persons to the status of things. Whenever racial discrimination [racism] exists it is a tragic expression of man’s spiritual degeneracy and moral bankruptcy. Therefore, it must be removed not merely because it is diplomatically expedient, but because it is morally compelling. 6

King's words echo biblical truth. The Bible's message was that all men are created Imago Dei. To bear witness to its truth, the message bore at least two pieces of the fruit of the Spirit: Love and Peace. The message was timely and indiscriminate. How else might it be accounted that a group of meek, non-violent, southern African-American pastors should have so successfully carried out the very same message that had been for more than two centuries violently suppressed? The imprimatur of God should have been detected from within the American Christian Church. After all, the boldness of vision sought inclusivity: the oppressed would invite the oppressors not only to repent and get clean, but to share a meal at the table of brotherhood. The demonstration of Christianity among men had not met so great an ecclesiastical opportunity. To the believing Church’s everlasting regret, the invitation went unaccepted. Like the strangers, vagabonds, and other initially uninvited guests of Luke 14 who are, after a while, invited to the great feast of the “certain man” because those originally invited made excuses, the message became an invitation to the nation to join in on the feast of brotherhood and righteousness – a “feast” that the Church made excuses not to attend. It is, again, a uniquely American message with deeply spiritual resonance. The brotherhood table of the sons of slaves and sons of former slaveowners was by invitation only. And King was issuing a call to all bigots, hatemongers, discriminators, as well as the indifferent – each of whom are more or less adversaries of righteousness - to make collective peace with their African-American brethren. It is this interpretation of Dr. King’s vision of brotherhood that holds lasting sway because of the apparent influence of the Spirit, the audacity of the message, and the realization that the time for brotherhood had, at long last, arrived in America. Where it differed was in the fact that this substantial call did not merely emphasize believing, but action – action from the Church first - and if unheeded, from the Nation. This action would be critically necessary for greatness to be achieved.

“When we allow freedom [to] ring… We will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last – free at last – Thank God Almighty we’re free at last!” 7

It is a sad fact of history that the evangelical, Bible-believing churches in America are, and remain, very much segregated institutions8. Dr. King himself once said that Sunday mornings are the most segregated time in America. This needed not to have been. I will discuss in a later chapter how this came to be, but for now it is important to understand just who Dr. King and the Racial Equality Movement were speaking to and why. There were more than 200 mainstream Christian denominations in American during the period of 1945-1960 and it is likely that all were very much aware of the plight of the Negro in America. Unequal social conditions could not have gone unnoticed by institutions presumably committed to bettering society through moral imperative. What appeared to be a tranquil Church on the shores of America was, in reality, a series of fragmented institutions – each going about their own business of advancing, through their own myopic lenses, the moral good of the land. Churches did not by and large care to become invloved in the what was perenially termed, “the Negro Question”, or the “Negro Problem”. But “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere9”, King once said. And it was this condition of injustice, either ignored, shied away from, or not understood by people of faith that lay beneath the surface of the Church. From thence, its legacy was to spoil the land by making it socially and legally unfruitful for those who differed not by their beliefs, but by their racial ethnicity. That racial division was as much an impenetrable reality among Christian believers and their churches is a sad legacy given the biblical imperatives to regard one another as brethren in the faith. Spiritual non-differentiation was apparently set aside for the predominant thought patterns of humanism, Christianity-ism, racial hierarchy and segregation. What is even more amazing is that not only were churches caught up in this thinking and reduced to silence on race matters, most churches could be expected to reaffirm the blessings of freedom and liberty bestowed to the state.

The Church, as Mark Noll put it, was not merely expected to be, but could be counted on to be silent in the face of state transgressions10. To the question of the institution of slavery, for example, there never existed in America’s history a unanimous charge from its churches against the state in its praxis. There were, to be sure, regional and spiritual charges against regional interests within the government, namely the New England abolitionists against the Southern slaveocracy; but even this was attentuated to the admissability of certain criteria within the debate: the question of freedom rather than equality for example, for the Negro slave. Under only the rarest of instances was it countenanced that the Negro, slave or free, was the White man’s equal; nor was it argued to any major extent by American churches at large that the Black man shared in the Imago Dei reality with the White man. Churches, with few exceptions, did not feel comfortable with race, social interaction, and its attendant messiness of civil rights and civil liberties. Many times was William Lloyd Garrison in the 1840s and 50s nearly physically thrown out of speaking halls and churches for his views on abolition and racial equality. With this historical legacy, and not answering the call to share at the table of brotherhood, the Church found itself on the outside looking in. This biblical metaphor is appropriate: while the table was set in the Master’s house, the children of the Master made their excuses.

Because Dr. King’s appeal to America was based in part on the Founding Documents, it was in part a deistic, Enlightenment message of humankind, a view that all men are the creatures of a benign Creator. But the message was provided its moral power by a thoroughly Christian faith and the belief that when our common humanity is taken seriously and morally - good can triumph over evil. The national achievement to be grasped in the post-WW II milieu of the 1950s and 60s was essentially an invitation to the “good”. And this goodness was based on the biblical principle of the Imago Dei – that all men were made in the Image of God and therefore having certain creaturely qualities based on God’s imprint - which cannot and must never be oppressed. And while the cojoining philosophical principle of humanity was based on a deistic rights-of-man thesis – it served as the handmaiden of the Imago Dei, it was the de facto legal and transparently moral underpinning of those documents which carried a binding, we-the-people contract that applied to all of America – regardless of ethnicity. It was in this vein that the Racial Equality Movement marched in the power of the Spirit, proclaiming and reclaiming the revelation and principles of these sacred and secular ideals.

Baruch Hashem! Maranatha! Soli Deo Gloria!

No comments:

Post a Comment