I did a paper on Black Liberation Theology that was rejected because it was perhaps too political. Ah well. I'll let you read and be the judge. Baruch Hashem!

The Liberation Theology of the Liberal Church

By Fred W. Ball, Jr., Ph.D.

Recently, the media has been focused on the presidential run of Barack Obama, the Illinois senator whose rise to popularity has been nothing less than meteoric. From a virtual unknown to the precipice of power in the free world, many Americans are trying to discover just who Mr. Obama is and what sort of values he holds. Simply put, America wants to know what Barack Obama believes before they give him power. One way of finding out who a man is and what he believes in is by examining his religious beliefs, practices and influences. And for the past twenty years Mr. Obama has been a member in good standing at the Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, Illinois, under the influence and teachings of its pastor, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright. Rev. Wright, who has very recently retired, has himself been in the center of a media firestorm because of his theological views and because of some anti-American sermons he has preached and in particular one given shortly after 9-11 invoking God to “damn” America. YouTube and other online newsgroups have run snippets from the sermon round the clock in which Rev. Wright makes clear that he is not concerned with biblical injunctions to love and redeem but to condemn and judge.

Perhaps many would be surprised that Rev. Wright’s rantings are not random and haphazard, but are deeply rooted in a theological point of view. And it is due to this aberrant theology that his views about race, ethnicity, and the American way of life should give anyone living in this country, Christian or not, cause for concern primarily because of how it may have influenced Barack Obama. While all believers are called to witness to the truth of the gospel, Jesus said that the servant is not greater than his lord; neither is he that is sent greater than he that sent him.1 In other words, every member of a church when he or she leaves the pews becomes a servant witness to what they have been taught and instructed from the pulpit. So it is that this principle of primary influence is one Christians ought to take seriously in the case of someone seeking the highest office in the land. Yet the question remains, as Mr. Obama has been “sent” by Rev. Wright, spiritually speaking, who has “sent” Rev. Wright theologically speaking?

The UCC and Christian Liberalism

Rev. Jeremiah Wright is a pastor in the United Church of Christ tradition. Quite apart from the biblical dogmatism of the Barton Stone/Alexander Campbell movement known as the Churches of Christ, the United Church of Christ (UCC) originates from a blend of New England Congregationalist and Evangelical and Reformed Church bodies in 1957. The official UCC website characterizes their theological tradition as follows:

“The denomination's official literature uses broad doctrinal parameters, honoring creeds and confessions as "testimonies of faith" rather than "tests of faith," and emphasizes freedom of individual conscience and local church autonomy. Indeed, the relationship between local congregations and the denomination's national headquarters is covenantal rather than hierarchical: local churches have complete control of their finances, hiring and firing of clergy and other staff, and theological and political stands.”2

Thus, the UCC polity does not, per se, subscribe to a tidy theological position but is noted for its absence of one. Whereas one congregation may be theologically moderate, another may be quite liberal in their views. Some UCC churches may be rightly called politically activist.3 One clue as to this theological non-centeredness is the sentence from their website that says that the creeds, confessions, and written formulations are not “tests of faith” but are “testimonies of faith”. This type of wordsmithing allows plenty enough theological wiggle-room to make any sort of doctrine acceptable. The trouble emerges on this point: if the doctrines are not tests but mere testimonies only, then the doctrines themselves are robbed of their compelling content. In other words, whatever is testified to as true for believer “A” may not be true for believer “B”. This places the UCC solidly in a whirlpool of theological relativism even within its own denomination. Similarly, its doctrinal statements, while paying homage to the Reformed tradition, are reduced to eloquent aphorisms since what they profess are not requirements for the believer to possess. In other words, one may have “faith” and a testimony - but the words of denotation, “I believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God”, for example, is not a test of anything. Contrast this with numerous passages in scripture which tell us as believers to confess specific propositions and values. Besides, if words mean nothing, why do we need a Bible? A testimony of faith is all we need. But in the UCC, all of this is OK. It is but another symptom of “anything-goes” liberal Christianity.

Liberation Theology becomes Black Theology

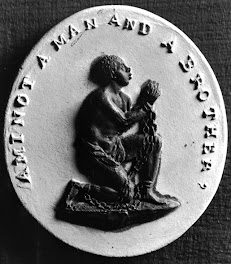

But Reverend Wright’s sermonic rant derives from theological leanings that are much more profound than Christian liberalism. His views are steeped in what’s known as Liberation theology. This theology originated during the turbulent 60s as a movement within Roman Catholicism with the principle aim of alleviating the suffering and oppression of the poor. While these are noble goals - and every Christian should be concerned with aiding the poor and eliminating oppression - advocates of Liberation theology tended to identify any and all oppression in strictly Marxist terms and have even justified the use of force, as Marxism permits, as an acceptable Christian means of eliminating oppression. But in its Marxist scheme, its application was also widespread: capitalism is identified as the enemy in the class struggle; males are identified as the enemy in the gender struggle; and Whites are identified as the enemy in the racial struggle.

Yet within this context, the very emphasis on class, gender, and race struggle works counter to the Gospel message – subverting it - by placing Marxist remedies, including violent uprising, ahead of Christian appeals to charity. Though this is not to say the Bible is set aside in Liberation theology, in fact, the primary proof-text its advocates misuse is Matt. 26:51-52, where Jesus declares that he has not come to bring peace but a sword. But very often in Liberation theology there is little difference in the sermonic call to Christian action and the kind of activism that leads to social unrest. As a result, Liberation theology often harms and defames Christianity by setting women against men, men against men, class against class, and race against race in clear violation of imperatives to show Christian love and model a unity of the brethren. It is no surprise then that, at least historically, Liberation theology found its most fertile ground in Latin America and in some African countries. But it could only be carried so far: some have said that the discrediting of Liberation theology in Latin America was due to the violent and bloody Nicaraguan and Salvadorian uprisings.[4] But in the United States, Liberation theology was instead embraced and then amplified by Marxist professors and liberal theologians from some of our country’s elite universities, colleges, and seminaries.

In particular, the views that Rev. Jeremiah Wright expounded from his pulpit are in large measure derived from the pen of Dr. James Cone, an African-American professor of theology at Union Theological Seminary whose principal work, A Black Theology of Liberation serves as the basis of what is called Black theology. And what is Black Theology? In short, it is Cone’s unique blending together of the 60s Black Power Movement with Barthian Christianity to form a single protest narrative. First, Cone posits the view that God identifies with the pain of the oppressed African-Americans in such way that racism then becomes a type of venial sin. In Black Theology, Cone argues that White people as a whole are not to be condemned as much as it is the “White Church” or “White Christianity” that should be identified as the oppressor of African-American Christianity. And why does Cone say this? Because Cone subscribes to the view that White Christianity represented and continues to represent itself as the moral institution from which America’s historic racial problems have been endorsed and now continue. Because White Protestant Churches largely disagreed or did not join hands with the aims of the Civil Rights Movement, White churches are therefore to be condemned for enabling White oppression of Black people and the moral voice of those people, the Black Church. But Cone goes further and suggests that God must ruthlessly judge White people for this particular sin or else. Or else what? Cone writes:

“…either God is for Black people or He is not; if He is against Black people, we must reject His love.” [5]

These are profound words. Not only that, Cone’s works are an endorsement of Black essentialism. This is the antithesis of White Aryanism – a belief that there is something essentially pure and holy to Black culture and Black skin. How influential is this? On CNN news recently, Rev. Wright tried to deflect criticism of his views by suggesting that criticism towards him and his ideas are in reality criticism directed at the Black Church.[6] An influential urban movement known as the Shrine of the Black Madonna, founded by Albert Cleage, goes so far to argue that the Holy Scriptures have been tampered with by Jews and Whites and that God and Jesus are actually Black Africans. This is an extreme view of this theological/racial identity theory, but it is not all far from the point Cone and others were making.

The Flaws of Black Theology

The view of Black Theology that racial oppression is a continuous and ongoing symptom of White Christianity is faulty on its face for four good reasons: One, oppression isn’t what it used to be. Blacks – who are overwhelmingly Protestant and Christian in the U.S. - have made political and economic strides in the past forty years that have been nothing short of spectacular in the history of civilized peoples. From chattel slavery a little over 150 years ago to an aggregate gross domestic purchasing power set at around 800 billion dollars last year is virtually miraculous.[7] That is to say, as America has prospered so also to a large degree has its Black population. African-Americans have been elected by voters of every hue to the highest offices in the land, appointed by White leaders to top-level executive posts at every tier of government, and are one of the primary influences in the entertainment, sports, and athletics industries. But perhaps more than that, the Black Church had been perhaps the crucial, moral voice to the ending of institutionalized racism both in the U.S. and abroad. So the problem of deep, strict oppression as Black theology identifies it is institutionally imperceptible. And this is not to say that racism is dead in the U.S., it isn’t; but historical racial oppression in its rawest, meanest form is quite dead.

Secondly, Black Liberation theology is fatally flawed by its reliance on the philosophy of racial essentialism. Any serious theology must refer to a God and a Redeemer who is absolutely above race and ethnic qualities if the message of salvation is to be carried out fully to the world. Even if God’s self-revelation is to the Jews only, a group Black Theology despises, the universal message of redemption is denied. But, as Paul wrote to the Romans, the gospel is to the Jew first and also the Hellenes, or non-Jews. And perhaps because Judaism rejected this message of redemption that God – in the fullness of time - caused the gospel to burst forth from Judea to Samaria and to the uttermost parts of the Earth. What else is the Great Commission but an appeal to every nation, kindred, and tongue? to slave and master? to patrician and plebian? to sinner and saint? But if Christ died only for the oppressed minority, i.e. Blacks, then there is indeed something special about Black folks that needs to be revisited in the scriptures. But the scriptures are plain that both Whites and Blacks need redemption and having once been redeemed - are Christ’s forever. Even on the face of it the premise is self-defeating: if Blacks are essentially pure, good, and holy, then why was Hitler’s claim about the essential purity of the Aryans wrong? Black Liberation theology cannot provide an answer to the universal problem of sin if Blacks are its only victims and Whites are the only perpetrators. Only advocating the eradication of Whites would solve this problem; but that would be the Hitlerian solution in reverse! Hate cannot be used to destroy hate. The scriptures tell us plainly that all have sinned and come short of the glory of God. Therefore, there is oppression – period – that must be dealt with. Not White oppression. And not just in Detroit, but in Darfur, too. The lies of the so-called purity of Africa-centered thinking must be dismissed as well. Bitter intra and cross-ethnic violence among neighboring tribes and people groups throughout Africa should also explode the myth that racial essentialism is the panacea for the oppressed Black soul in America. Oppression knows no ethnic bounds.

Thirdly, Black Liberation Theology is virtually a stranger to the biblical concepts of grace and love. Blacks must understand from their history books that Whites have been given a grace that they have not always shared in the way that Christ would have them share it. America’s Christian history has not always been kind to African-Americans. And though most White Christians and Christian denominations opposed Dr. King and his very moral message of ethnic reconciliation and justice it does not follow that White people are therefore guilty of the unpardonable sin. To be sure, the nasty symptoms of “human group” sin: racial oppression, ethnic prejudice, and the like, are very much barriers to agreement and harmony in the Body of Christ, and the Church needs the passion of those who hunger and thirst after righteousness to change this and conform the Church to Christ’s standard. But the nature of sin is its self-deception that we alone – and our group - are free from it. We can see the mote of racism in our brother’s eye far easier than we notice it in our own. Hate begets hate much more than it can produce love. Grace allows the believer to appeal to the righteousness of Christ and accept in himself something of the burden of the Savior’s unjust suffering. We must all work out our salvation with fear and trembling lest we ourselves fall into the same snare as the disobedient and the hypocrite. Historic racial and ethnic grievances should be something the Church wrestles with, acknowledges, and unites together to destroy and then forgive one another. White people are not the enemies of Black people; neither is the so-called White Church an enemy of the so-called Black Church – no matter how often the Rev. Wright and others traffic in these lies. But rather it is the gift of God to grant us as individuals and members of ethnic groups the divine grace to endure each group’s flaws and manners. But with one caveat: that we should all go and sin no more.

Fourth, Black Theology is actually a type of humanism masquerading as Christian justice. Though the final authority and judge of the Body of Christ is Jesus Himself, in actualizing Black theology Christ’s authority is solidly rejected. By default then, men must defer to other men to remedy the problem of group sins and oppressions. But who among us is without sin to be a fair judge? Unfortunately, sin is the universal problem that Black Theology wants to place only on White folks. (How ironically racist is this type of judgment?) Hamlet said, “…treat every man as he deserves and who shall escape a whipping?” The very nature of Christian grace is that it allows us to correct our faults without the instant justice of Hell we each deserve. African-Americans have a lot to be thankful for and a lot to thank others for overlooking. And we seek to die daily to those sins that easily beset us in the hope that our habits as well as our hatreds are not called into account. Yet if man is truly the measure of all things - as humanism claims and Black Theology suggests - then our remedies to racial injustice can only be human ones. But we must also ask this question: is there truly a just remedy to racism and ethnic oppression outside of the application of divine love to the human heart? If so, aren’t we rejecting the God who, as the scripture says, “shall judge the secrets of men by Jesus Christ according to my gospel.”? [8]

Reverend Jeremiah Wright would have us all believe that the struggle against Black oppression is as real and vital as it was in the 1960s. And perhaps Barack Obama heard in Rev. Wright’s sermons and in the UCC fellowship the emotional roots of an identity struggle that he himself is seeking to resolve inwardly, having had no father to guide him. But clearly, Rev. Wright and the UCC are in the wrong, having not solved their own identity struggles, nor gotten over their failed Marxist theories, but have sought to cloak their protests with a veneer of Christianity. The need for Black churches to preach a political message of hate rather than accept a Christ who loves is perhaps the final mystery of iniquity in this sad saga. And keeping all of this in mind, let us remember that while love covers over a multitude of sins, we can’t help but shake our heads in wonder at the supreme irony that pastors like Rev. Wright are also the beneficiaries of a great country that grants them the freedom to preach their hatred of it.

Notes:

1 John 13:16

2 The United Churches of Christ website: www.ucc.org

3 Northern California/ Nevada Conference of the UCC website: www.ncncucc.org/mission/index.html

[4] AD2000: A Catholic Monthly Vol 1 No 9 (December 1988 - January 1989), p. 12

[5] William R Jones, "Divine Racism: The Unacknowledged Threshold Issue for Black Theology", in African-American Religious Thought: An Anthology, ed Cornel West and Eddie Glaube. (Westminster John Knox Press), 2003, pp. 850, 856.

[6] “Still More Lamentations From Jeremiah” from Washington Post article, by Dana Milbank. Tuesday, April 29, 2008; Page A03

[7] “Two Black Americas” from Washington Post editorial, by Eugene Robinson.

Friday, April 4, 2008; Page A23

[8] Romans 2:16

© 2008 All Rights Reserved

Tuesday, June 3, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment